8

Hugh McGuire builds tools and communities where book publishing and the web intersect. He is the founder of PressBooks (on which this book has been built), and LibriVox.org, a community of volunteers that has created the world’s largest free library of public domain audiobooks. You can find him on Twitter at @hughmcguire.

Sometime last year, I had a moment that felt like a profound revelation, and as with all such revelations of mine, I got me to Twitter and posted there:

The distinction between “the internet” & books is totally totally arbitrary, and will disappear in 5 years. Start adjusting now.

It seems almost trivial as far as epiphanies go now, but still at the time it was a kind of shocking realization. If you think about “books”—which are, more or less, collections of words, sentences, and images arranged in a particular way—and compare them to, say, websites—which are, more or less, collections of words, sentences, images, audio, and video, arranged in a particular way—there is a jarring distinction that presents itself. We have decided, for mostly historical reasons, that collections of words and sentences of one kind go into a “book” and collections of words and sentences of another kind go onto the “Internet.”

And the question we must ask is: Why, exactly, have we decided things should be this way? Why is it that only certain kinds of words and sentences are supposed to get sent to printers, stamped in ink on a page, stuffed and bound between covers, and sold in physical stores? (Or, sold through a Kindle, for that matter?) Why is it that other kinds of words and sentences are instead supposed to get typed into a keyboard, sent to a server somewhere, and then transmitted in one way or another to appear on the screens of computers and smartphones of readers around the world? What is the distinction between these kinds of words?

One answer came, from a fellow Twitterer, Damien G. Walter, in response to my initial post.

There are two powerful ideas behind this point of view. One has to do with quality of work and attention to detail. Books, this position claims, contain “important” work.

Whereas the Internet? The Internet is the domain of celebrity gossip, flamewars, self-obsessed or half-crazed bloggers, and even Twitter.

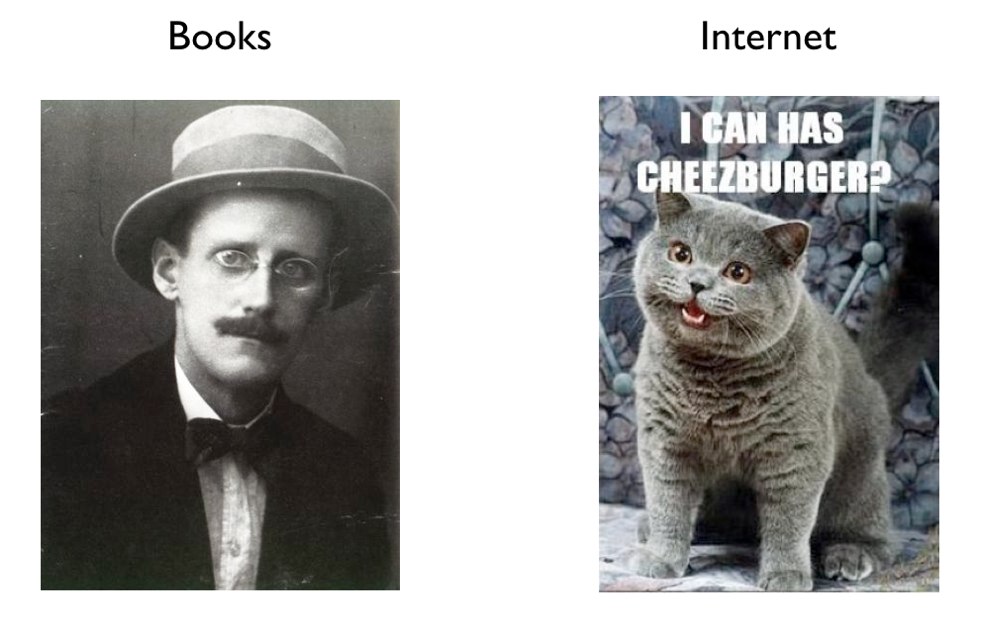

I call this the Joyce/Cheezburger position.

So quality of the words (“which are written, researched, edited, marketed” for books versus “ego noise” for the Internet) is one distinction between “books” and the “Internet,” according to this view.

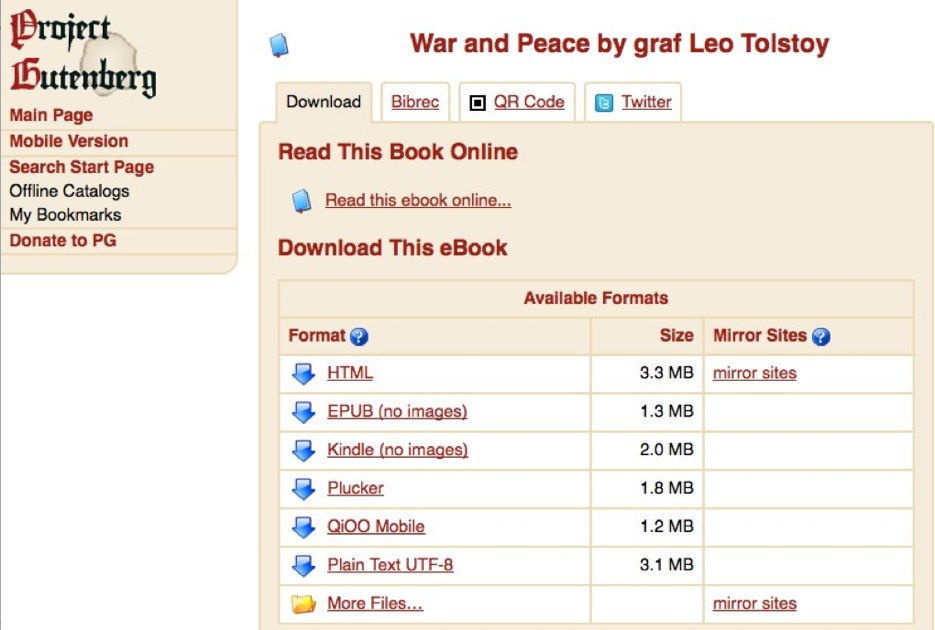

On the question of quality of words, though, it’s clearly not the case that books, which are written, researched, edited, and marketed, can’t be on the Internet. Indeed, one of the first ever web sites, Gutenberg.org[1]—started by Michael Hart in 1971—is dedicated to making public domain books freely available on the Internet.

Still, given that Gutneberg.org has been around for 40 years, it’s worth asking why books on the Internet have not been particularly popular among the mass consumer market. I think the reason is simple, and it has little to do with quality of the words or cost. Until recently, most people didn’t seem to want to read books on screens. I was one of those people. I read news and blog posts and Wikipedia articles and emails on a screen, but I just didn’t like reading long-form text—even the great, free ebooks from Project Gutenberg—on a screen.

So there was really not much incentive for publishers to make books into something that could be read on a screen, since very few people wanted to read books from screens. Instead people seemed happy to read books on paper and spend their time on the Internet making funny pictures of cats, blogging about their breakfast, and contributing to the world’s largest encyclopedia.

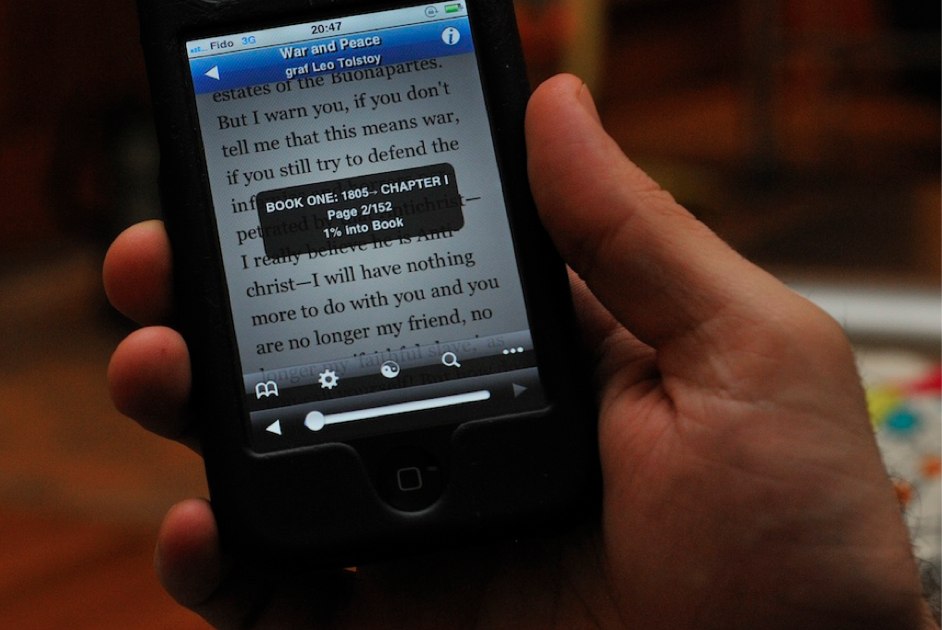

Then came some new devices, with the full force of marketing giants behind them: Amazon’s Kindle, the Nook, and for me, the revelation was the iPhone. If you can believe it, the first ebook I read was War and Peace, on my iPhone. I loved it. The experience was—for me—comfortable, convenient, pleasant, and revelatory. I was not a convert because of dogma, but rather because I just liked reading on this digital device, and my guess was that once other people experienced reading on this new breed of device, ebooks—with their myriad advantages—would win out.

And now, of course, ebooks have arrived, in force. In 2008—when I read War and Peace on my iPhone—about 1% of trade book sales in the US were ebooks. In 2011 the number was close to 20%. Many expect 50% of trade sales to be ebooks by 2015, if not sooner. Books may not yet be on the Internet in great numbers, but they sure are in people’s Kindles, iBooks, Nooks, and Kobos.

How We Think about Ebooks

While we are in the process of seeing a massive shift in the technology used to read long-form content, to date we’ve actually seen very little real disruption in the structures (rather than mechanisms) by which people get their books to read. That is, the current structures of getting a book into a reader’s hands (publisher -> seller -> reader) looks a lot like the print world. Instead of publishers producing a print book and shipping it to a book store that manages the sales to consumers, publishers now produce an EPUB and send it to an online retailer, which manages sales to consumers.

For all the main players (publishers, retailers, and readers), the ebook business sure looks a lot like the print book business.

And yet the stuff ebooks are made of is very different from what print books are made of.

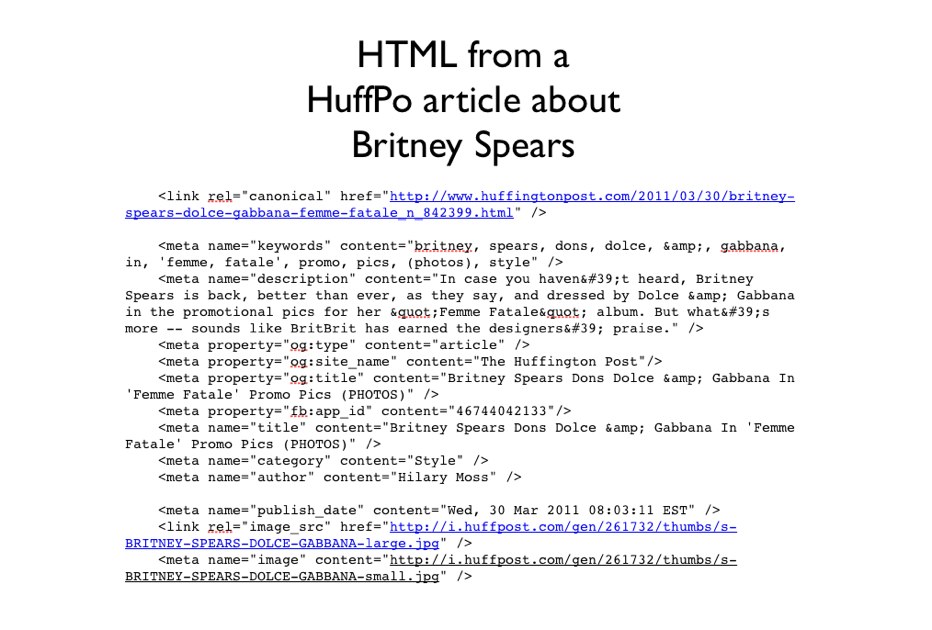

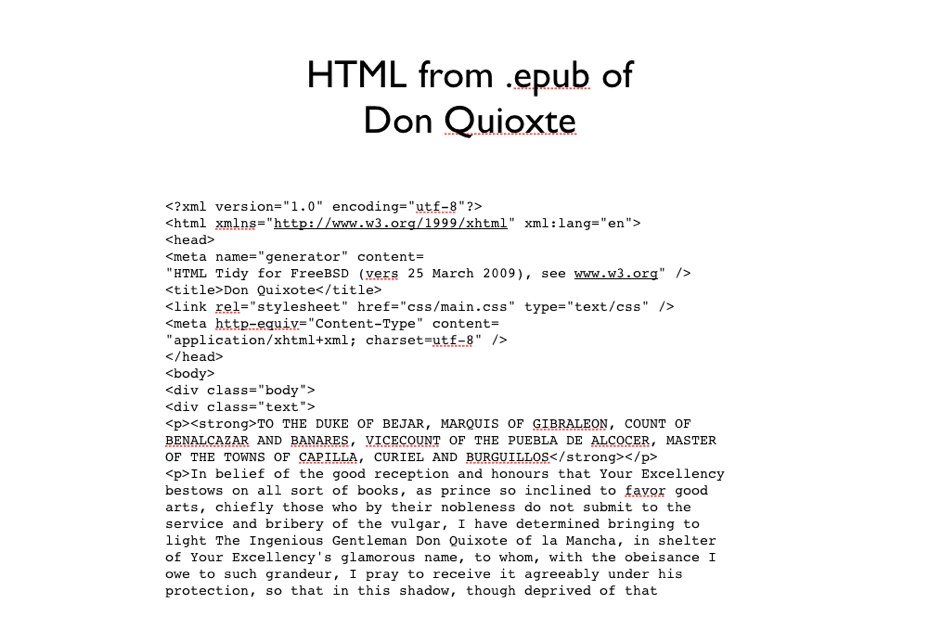

Ebooks are, in fact, a lot more like websites than like print books. Or rather: they are almost exactly like websites. Ebooks are built in HTML, which is the programming language (or mark-up language, if you prefer) used to make websites. There really isn’t that much difference between the stuff we use to build, say, an article about Britney Spears in the Huffington Post, and an EPUB of Don Quixote.

[Huffington Post Web HTML]

As we said before, books are just collections of words and media, with a certain structure—chapters, headings—and a bit of metadata—an author, a cover image, a title. If you are making a digital book, it makes sense that you would use the same programming language that you’d use to make a website, since that’s pretty much what a website is.

But there is a catch: Publishers are afraid of websites and the Internet. And rightly so. The Internet gobbles up existing business models and spits out chaos. We’ve seen this with music and with newspapers and movies. Because the Internet could radically change the book publishing business, publishers are right to worry about it.

The solution to date, which addresses this legitimate fear, is to “constrain” ebooks. This means that a lot of the things we take for granted on most websites are just not possible with books. Copy/paste, sharing passages, and generally moving files from one place to another is much harder with ebooks than with other digital goods, because of a combination of constraints in the EPUB format, digital rights management, and device/platform lock-in.

ebooks may be built out of the same stuff as the Internet (that is, HTML), but to date we’ve managed to keep them relatively tame, compared to the wild and wooly world of the Web.

This is a good thing if you have an existing business model you wish to protect (and publishers and authors certainly do, rightly so).

But there is a cost to this protection, because in order to achieve this similarity with the past, we’ve intentionally crippled ebooks. We’ve constrained ebooks so they act more like print books and less like the Web.

Here are just some of the things we expect to be able to do with things on the Internet that we can’t do with ebooks:

- copy/paste

- link to a specific chapter or page

- search for text on the Internet and land on the ebook

- leave a comment or feedback in a central place

- easily query an API about that ebook

- easily search and extract geographic data from an ebook

- etc!

Here is a question: if you can do certain things with a print book and other things with an ebook, and different kinds of things with a book on the Web, which of these options is more valuable to you as a reader?

Having just ebooks and print books? Or having ebooks, print books, and books on the Web? My answer is, from a pure mathematical view: print, ebook, and Web.

P +E < P+E+W

So what kinds of things might come about if books are connected to the Web? The truth is, we don’t really know. And that is precisely why I believe books will end up on the Web.

Because when things are made accessible on the Web, smart people start to build exciting things. New things get born that we never would have imagined. We’ve seen this time and time again: think about what happened when we started sending correspondence through email, conversation through Twitter, when Google put maps on the Internet and made those maps available through an API. Making things available on the Web gives birth to new and exciting things we can’t yet imagine.

The market economy and the innovative spirit of the Web are great at rewarding those who find ways to deliver more value to people. There will be immense commercial and creative incentive for new publishers to put books on the Web, because there is just more value for readers there. We don’t know what the business models will look like. Subscription books? Advertising? Upselling other products? Serialized books? Something altogether different? We don’t know yet, but eventually courageous new publishers will find out.

Old publishers will follow or perish.

And yet some people find the idea that books will be on the Web to be heretical. Because the Web is filled with lolcatz and ego noise.

But the question isn’t what stupid things people have put on the Web in the past, but what great things we could do if books were connected on the Web in the future. That’s what sets people who love books, and the Web, to dreaming.

Give the author feedback & add your comments about this chapter on the web: https://book.pressbooks.com/chapter/book-and-the-internet-hugh-mcguire